»Ein Bild, das ein bisschen übersteht«

SLEEPING STRANGER

Keong-A Song erfindet Geschichten, die, wie sie sagt, »in ihrer Fantasie lebendig« sind. Unsere Eingangstür in diese Welt waren bislang ihre Zeichnungen. Die Geschichten der Künstlerin spielen nicht in einer idyllischen Märchenwelt: Zwar befinden wir uns stets in einem traumhaften, phantastischen Kosmos, doch er enthält immer eine menschliche (und manchmal gar allzu menschliche) Nuance. Die leicht verschobene Welt der Künstlerin ist nämlich bevölkert von anthropomorphen Gestalten mit Tiergesicht und häufig typisch menschlichem Charakter. Humor und Behutsamkeit, Feinsinn und Selbstironie sind mit am Werk, wenn Keong-A Song sich aus einer gewissen Distanz heraus die Welt neu erdenkt. Sie verwendet überwiegend Tusche und Aquarellfarben. Manchmal arbeitet sie sehr minimalistisch, die sparsame Linienführung und die mageren Informationen verweisen auf die Karikatur; andere Zeichnungen sind unendliche Welten voller winziger Details, von denen man, je mehr Zeit man ihrer Arbeit widmet, immer wieder neue entdeckt.

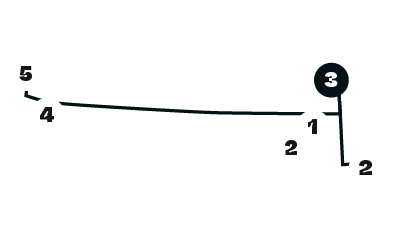

Sleeping Stranger ist das erste Werk der Künstlerin im öffentlichen Raum. Es zeigt ein unbekanntes, ein namenloses, unkenntliches Ungeheuer, das auf Reisen ist. Eine Etappe auf dieser Reise ist nun Lorentzweiler. Müde sucht das Ungeheuer nach einem Schlafplatz und findet ein verlassenes Häuschen: Hier wird es ein paar Nächte verbringen. Das Ungeheuer muss riesig sein, denn schon sein Schwanz, der »ein bisschen übersteht«, ist gigantisch. Wenn man sich dem schlafenden Ungeheuer nähert – hört man es schnarchen.

Dieses »leichte« Überstehen wird zum Ausgangspunkt der Überlegungen, die die Künstlerin zum Begriff des Eigentums anstellt. Dieses Bild vom überstehenden Schwanz des Ungeheuers regt sicherlich die Phantasie von Kindern (und Erwachsenen) an, aber zugleich stört es auch, denn ganz offenbar hat der Sleeping Stranger sich ein Haus angeeignet, das ihm nicht gehört.

Schon seit den ersten Darstellungen in der Antike ist das Ungeheuer nie allein, sondern häufig dialektisch seinem symbolischen Gegenpart gegenübergestellt oder von ihm begleitet: dem Helden, der für eine ursprüngliche Tugend streitet. Das Ungeheuer symbolisiert die Elemente des Bösen, die der Held bekämpfen muss, um das kosmische Gleichgewicht wiederherzustellen. Hier aber sind Ungeheuer und Held zu Einem verschmolzen. Das Wesen, das in anarchistischem Gebaren einen Raum besetzt, der ihm nicht gehört, mag durch seine Größe bedrohlich wirken, doch zugleich ist es ganz harmlos: Es schläft ja nur. Es braucht eben nur einen ruhigen, sicheren Ort zum Schlafen, und dafür hat es sich dieses Haus ausgesucht, das zufällig der Gemeinde Lorentzweiler gehört.

Damit wird Lorentzweiler zu dem Ort der Phantasie, an dem Keong-A Song fragt, ob der Begriff des Eigentums überhaupt mit dem Leben der Natur kompatibel ist. Die drei großen Theoretiker des Eigentums (John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau und Karl Marx), die alle eine »natürliche« Ausgeglichenheit zwischen dem Begriff des Eigentums und der Befriedigung individueller oder gesellschaftlicher Bedürfnisse postulieren, haben in dieser Gleichung die Natur und die gesamte nicht-menschliche Welt nämlich alle schlicht vergessen. Tatsächlich baut unsere menschliche Gesellschaft seit Jahrhunderten auf eben dieser Grundlage auf: der Aneignung des natürlichen Raums. Sleeping Stranger nimmt in diesem Zusammenhang das »Nutzungsrecht« für einen Raum in Anspruch, um ein ganz natürliches Bedürfnis zu befriedigen: das Bedürfnis nach Schlaf. Es steht damit für die natürliche Pflanzen- und Tierwelt, die allein durch ihr Verhalten die Frage nach dem Eigentum aufwirft, indem sie ihre Rechte einfordert.

Das Schnarchen des Monsters ist die humorvolle Brücke – auch der Humor prägt Keong-A Songs Werk – zu dem sanften Spott, mit dem sie den Alltag gerne betrachtet. Im Zusammenleben mit einem Mitmenschen müssen wir unseren privaten Raum und unsere ganze Intimität teilen. Dieses unvermeidliche Teilen etwa in den Stunden des Schlafs kann Probleme mit sich bringen, die sich möglicherweise deutlich abgrenzen von unserer Liebe zu diesem Menschen, der in »unser« Leben eingedrungen ist.

« Faire une image qui dépasse un peu »

SLEEPING STRANGER

Keong-A Song écrit des histoires qui sont, comme elle le dit : « vivantes dans son imaginaire ». La porte d’entrée pour nous dans ce monde était jusqu’à présent ses dessins. Les histoires de l’artiste ne sont pas des contes de fées où tout est idyllique : ce sont certes des univers oniriques, fantastiques, mais dans lesquels s’insère toujours un glissement humain (parfois même trop humain). Le monde légèrement décalé de l’artiste est en effet habité par des êtres anthropomorphes qui ont des visages d’animaux et souvent des caractères typiquement humains. Avec humour et tendresse, subtilité et autodérision, Keong-A Song prend ainsi une certaine distance du monde afin de le penser. Elle dessine surtout à l’encre de Chine et à l’aquarelle. Ses dessins sont parfois très minimalistes, crées avec une économie du trait et de l’information qui renvoie aux caricatures et d’autres fois ils sont des univers infinis, peuplés de détails minuscules que l’on ne cesse de découvrir en accordant du temps à son travail

Sleeping Stranger est son premier projet dans l’espace public. C’est l’histoire d’un monstre inconnu, anonyme, non-identifiable, qui voyage. Ce monstre passe au cours de son voyage par Lorentzweiler. Il est fatigué et veut dormir un peu, il trouve alors une petite maison abandonnée et décide d’y passer quelques nuits. Le monstre doit être assez grand, car sa queue qui « dépasse un peu » est gigantesque. Lorsque l’on se rapproche du monstre endormi : on entend son ronflement.

C’est à travers ce « léger » dépassement que se développe la réflexion de l’artiste autour de la notion de propriété. Cette image de la queue du monstre qui dépasse provoque certainement l’imaginaire d’enfants (et d’adultes), mais elle dérange aussi, car le Sleeping Stranger s’est vraisemblablement emparé d’une maison qui ne lui appartient pas.

Dès les premières figurations antiques, le monstre n’est jamais seul, il est souvent dialectiquement opposé à, ou accompagné par, son double symbolique : le héros qui se bat pour une vertu fondatrice. Le monstre symbolise les éléments néfastes contre lesquels le héros doit se battre pour rétablir l’équilibre cosmique. Ici, monstre et héros sont la même entité. Celui qui occupe, comme un anarchiste, un espace qui ne lui appartient pas, est peut-être menaçant par sa taille, mais il est en même temps inoffensif : il ne fait que dormir. Il a juste eu besoin d’un espace calme et protégé pour se reposer et il s’est emparé de cette maison qui appartient à la commune de Lorentzweiler.

Lorentzweiler devient ainsi la ville imaginaire dans laquelle Keong-A Song pose la question de savoir si l’idée de propriété est réellement compatible avec la vie de la nature. Car les trois grands penseurs classiques de la propriété (John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau et Karl Marx), qui ont tous établi une adéquation « naturelle » entre le concept de propriété et la satisfaction des besoins individuels ou sociaux, ont tous oublié dans l’équation la nature et tout le vivant non-humain. Notre société humaine s’est en effet construite au fil des siècles sur cette base d’appropriation des espaces naturels. Sleeping Stranger s’octroie dans ce contexte le « droit d’usage » d’un espace pour satisfaire un besoin naturel : dormir. Il représente ainsi le monde naturel, animal, qui pose par son comportement la question de la propriété en revendiquant ses droits.

Le ronflement du monstre est le passage humoristique, qui caractérise aussi le travail de Keong-A Song, vers la dérision tendre avec laquelle elle aime concevoir la vie quotidienne. Lorsque l’on vit avec une personne, notre espace privé et notre intimité la plus intime doivent être partagés. Ce partage inévitable, par exemple des heures de sommeil, pose des problèmes qui sont différents de l’amour que l’on peut éprouver pour la personne en question et qui est entrée dans « notre » vie.

”Making a Picture that Sticks Out a Little”

SLEEPING STRANGER

Keong-A Song writes stories that are, as she says, ‘alive in her imagination’. For us, her drawings have always been the gateway to this world. The artist’s stories are no fairy tales where everything is idyllic. They are certainly dreamlike, fantastic worlds, but they always include a human (sometimes even too human) twist. The artist’s slightly offbeat world is indeed inhabited by anthropomorphic beings with animal faces and often typically human characteristics. By using humour and tenderness, subtlety and self-mockery, Keong-A Song distances herself from the world in order to reflect upon it. She draws mainly in Indian ink and watercolour. Her drawings are sometimes very minimalist, created with an economy of line and information that refers to caricatures. Other times they are infinite universes, populated with tiny details that one never ceases to discover over time.

Sleeping Stranger is her first project in the public space. It is the story of an unknown, anonymous, unidentifiable monster who travels. On his journey, the monster passes through Lorentzweiler. He is tired and wants to sleep, so he finds a small, abandoned house and decides to spend a few nights there. The monster must be quite big, because his tail, which ”sticks out a little”, is gigantic. When you get closer to the sleeping monster, you can hear him snoring.

It is through this “slight” protrusion that the artist’s reflection develops on the notion of property. This image of the monster’s tail sticking out certainly triggers the imagination of children (and adults), but it is at the same time disturbing, because the Sleeping Stranger has probably taken over a house that does not belong to him.

From the earliest ancient figurations, the monster is never alone. He is often dialectically opposed to, or accompanied by, his symbolic double: the hero who fights for a founding virtue. The monster symbolises the harmful elements against which the hero must fight to restore cosmic balance. Here, monster and hero are the same entity. The one who, like an anarchist, occupies a space that does not belong to him, is perhaps a threat because of his size, but at the same time he is harmless: all he does is sleep. He was just looking for a quiet and protected space to have a rest and he took over this house which belongs to the municipality of Lorentzweiler.

Lorentzweiler thus becomes the imaginary setting in which Keong-A Song wonders whether the idea of property is really compatible with nature’s life. For the three great classical thinkers of property (John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Karl Marx), who all established a “natural” adequacy between the concept of property and the satisfaction of individual or social needs, also all forgot nature and non-human life in the equation. Over the centuries our human society has indeed been built on this foundation of appropriation of natural spaces. In this context, Sleeping Stranger grants himself the “right to use” a space to satisfy his natural need for sleep. He thus represents the natural, animal world, whose behaviour raises the question of property while at the same time claiming his rights.

The snoring monster is the humorous transition, which also characterises Keong-A Song’s work, towards the tender derision with which she likes to view everyday life. When living with someone, our private space and most intimate intimacy must be shared. This unavoidable sharing, for example of sleeping hours, poses problems that are different from the love we may feel for the person in question who has entered “our” life.

Der Mensch hat klare Regeln, was das Eigentum und das Recht auf den privaten Raum betrifft. Für diese Ausstellung gehe ich von der Idee aus, dass ein Lebewesen in Lorentzweiler, einer verschlafenen Gemeinde, ankommt, um sich dort auszuruhen. Da es unsichtbar bleiben und nicht stören will, lässt es sich in einem verlassenen Anwesen nieder. Sein langer Schwanz, der überall herausragt, und sein Schnarchen beunruhigen die Passanten. Sein Zustand völliger Armut stört die Bewohner, die nicht wissen, wozu es in der Lage ist und wie es aussieht.

L’être humain a des règles bien définies sur la propriété et le droit de l’espace privé. Pour cette exposition, je pars de l’idée qu’une créature vivante arrive à Lorentzweiler, commune endormie, non propice pour demander de l’aide, pour s’y reposer. Voulant rester invisible et ne pas déranger, elle s’installe dans une propriété abandonnée. Sa longue queue qui dépasse de partout et son ronflement inquiètent les passants. Son état de pauvreté totale dérange les habitants, qui ne savent pas de ce qu’elle est capable de faire et à quoi elle ressemble.

Human beings live according to well-defined rules about property and the right to private space. My proposal for this exhibition is based on the idea that a living creature arrives in Lorentzweiler, a sleepy town, hardly supportive of aid seekers, to have a rest. In its effort to be invisible and not to disturb, it settles down in an abandoned property. Its long tail sticks out everywhere and Passers-by are concerned by its snoring. Its state of total poverty disturbs the inhabitants, who do not know what it is capable of doing nor what it looks like.

Keong-A-Song wurde in Seoul, Süd-Korea geboren. Im Jahr 2000 schreibt sie sich an der Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Art et de Design in Nancy, Frankreich, ein. 2005 erhält sie ihr Abschlussdiplom DNESP. Seitdem arbeitet sie als Künstlerin und Illustratorin sowie als Autorin, wobei sie das Schreiben und Zeichnen kombiniert. Keong-A-Song hat zahlreiche Bücher veröffentlicht. Für Wooow!!! erhielt sie 2018 den Lëtzebuerger Buchpräis für das beste Kinder- und Jugendbuch. Seit 2012 wohnt und arbeitet sie in Luxemburg und hat an verschiedenen Projekten (Ausstellungen, Werkstätten, Zusammenarbeiten, Auftragsarbeiten) mit der Mehrzahl der Kunstinstitutionen in Luxemburg zusammengearbeitet. Ihre Arbeiten haben sie auch ins Ausland geführt wie zur Fondation Boghossian – Villa Empain, Brüssel, zum Luxemburger Pavillon bei der Biennale von Venedig, zum Koreanischen Kulturzentrum in Brüssel sowie zum Musée national Marc Chagall in Nizza, Frankreich.

Keong-A-Song est née à Séoul en Corée du Sud. Elle arrive en France en 2000 et suit des études à l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Art et de Design de Nancy, où elle obtient en 2005 le diplôme DNSEP. Depuis lors, elle travaille comme artiste et illustratrice et s’investit également dans l’édition où elle combine écriture et dessin. Elle a publié de nombreux livres dont Wooow !!! qui a obtenu en 2018 le Lëtzebuerger Buchpräis pour le meilleur livre pour enfants et adolescents. Depuis 2012, Keong-A-Song vit et travaille au Luxembourg où elle réalise et participe à différents projets (expositions, ateliers, commandes, collaborations) avec la plupart des institutions d’art au Luxembourg ainsi qu’à l’étranger, notamment avec la Fondation Boghossian – Villa Empain, Bruxelles, le pavillon luxembourgeois à la Biennale de Venise, le Centre Culturel Coréen Bruxelles et le Musée national Marc Chagall, Nice, France.

Keong-A-Song was born in Seoul, South Korea. She arrived in France in 2000 and studied at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Art et de Design in Nancy where she obtained the DNSEP diploma in 2005. Since then she has worked as an artist and illustrator and has also been involved in publishing, thus uniting writing and drawing. She has published many books including Wooow!!!, which was awarded the Lëtzebuerger Buchpräis in 2018 for the best children’s and adolescents’ book. Since 2012 she lives and works in Luxembourg, where she created and participated in various projects (exhibitions, workshops, commissions, collaborations) with most cultural institutions in Luxembourg and abroad notably with the Boghossian Foundation – Villa Empain, Brussels, the Luxembourg pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the Korean Cultural Centre Brussels and the Musée national Marc Chagall, Nice, France.